The Maiden from Hainholz

A Glimpse at the Terror of a Medieval Epidemic

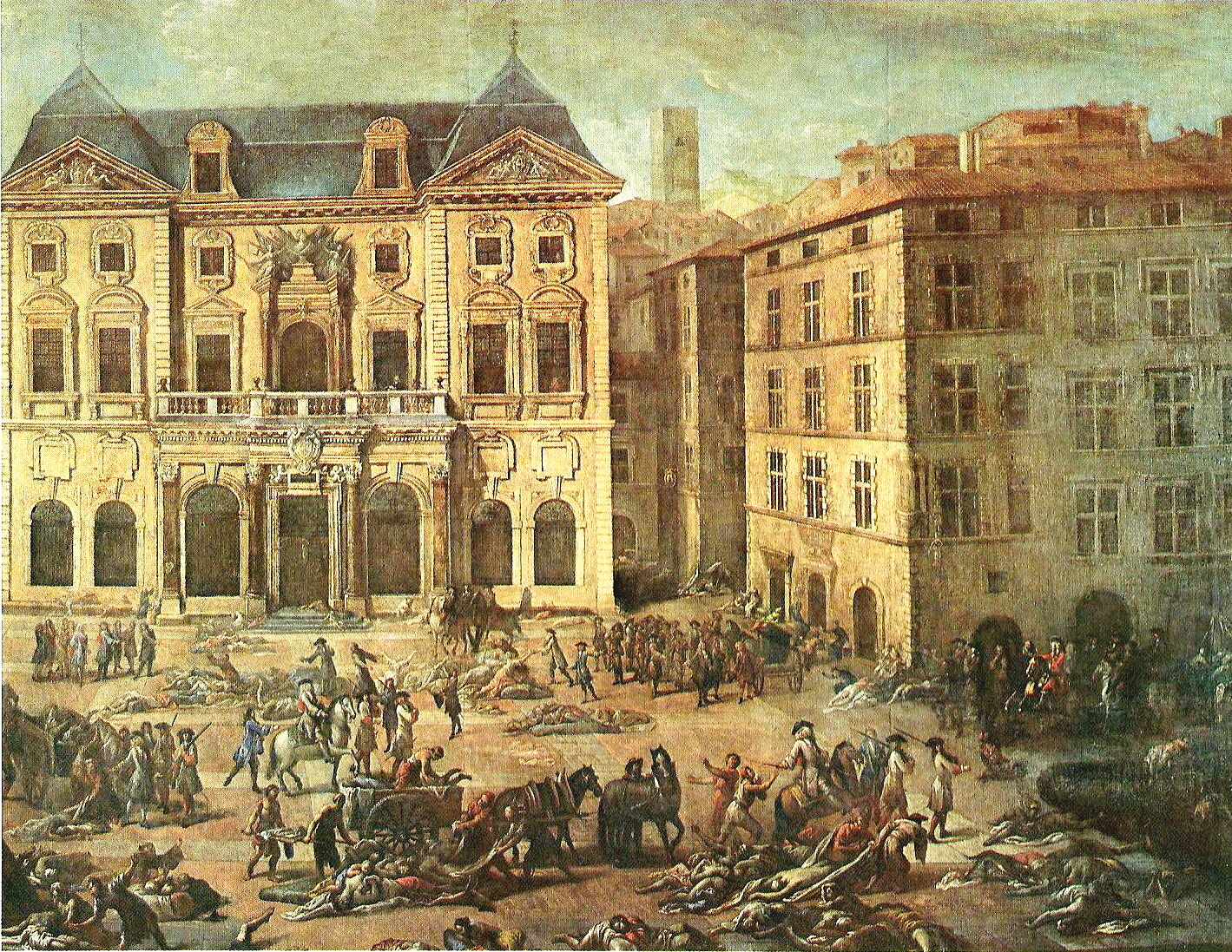

The year is 1665. Poland has been at war with Russia for thirteen years, and England is engaged in a sea war with Holland. Charles II was crowned as King of Spain, at the mere age of three. It is one year prior to the Great Fire of London. Among the gedolei yisrael living in that era were the Turei Zahav, in Lemberg, Podolia; the Kikayon D’Yonah, in Metz, France; Rabbi Moshe Rivkah’s, author of the Be’er HaGolah, in Vilna, Lithuania; Rabbi Shmuel Kaidonower, author of the Birkas HaZevach, in Fürth, Bavaria; Rabbi Ephrayim HaCohen, author of the Sha’ar Ephrayim in Vienna, Austria and Rabbi Avraham Abbele Gumbiner, author of the Magen Avraham in Kalisz, Greater Poland.

The Great Plague London 1665

In Europe, a deadly epidemic known as the Bubonic Plague was ravaging the Continent. England, as an island, moved to protect itself by denying all foreign ships entry to English territory. Two marine boats were sent to the Thames estuary, to control the movement of ships, all of which had to stop at Canvey Island for thirty days before entering England. Ships arriving from unaffected areas or those that had already passed the quarantine, were given a permit to travel through the River Thames to London.1Stephen Porter, The Great Plague.

The Move to Hameln

Winter 1664

One of the important chronicles of Jewish life in the Middle Ages is the diary kept by Mrs. Glickel of Hameln, in which she wrote about her life as a Jewish mother in great detail, raising a large family, her first and second marriages and the affairs of the prosperous business she operated. She spoke with honesty and pathos of the joys and challenges, triumphs and disappointments of her eventful life. The diary is written in the old-style Yiddish that was current in the 17th century.2The Memoirs of Glückel of Hameln, Book III.

As the following excerpt from her diary opens, she has just moved from Hamburg to Hameln with her first husband, R’ Chaim Halevi, a truly righteous and G-d-fearing man.

Succos in Hannover

I just gave birth to my daughter Matti.3She didn’t survive childhood, she died before Gluckel wrote her diary. She is a beautiful child as you will see. At the time of her birth, talk of Shabsai Tzvi had begun spreading…4Gluckel, dwelves here into discussion about Shabsai Tzvi.

When I was still in the postpartum period, I started hearing rumors about a plague. The plague took over so strongly that three or four houses were overtaken by the disease that every member of these households died, and these homes remained empty. It was tragic to see. Now all the wealthy community members have moved from Hamburg to Altona.5Altona is today part of Hamburg. In Gliskel’s times, it was a separate town, the border of nearby Denmark shifted many times, sometimes including Altona within its borders.

We decided to move with our children to Hameln,6About 190 Kilometers away, that is about 120 miles. where my father-in-law lived. A day after Yom Kippur, we traveled to Hannover7Enroute, about 45 kilometers from Hameln, that is about 30 miles. where we stayed at my brother-in-law, R’ Avraham’s home. They didn’t let us travel further because they felt it was too close to Succos, so we remained in Hannover over Yom Tov.

The Swelling

I had three children at that time: Tzipor8That is how she was named, not Tzipporah. who was four years, Nosson, two years old and the baby Mata, who was only eight weeks.

In my brother-in-law, Leib’s house, there was a shul, where he and my husband were davening. I was downstairs, dressing my daughter Tzipor, when I noticed she was very uncomfortable when I touched her.

I said to her: “Tzipor dear, what’s bothering you?”

“Mother,” she answered, “I’m in a lot of pain under my arm.”

I looked under her arm and saw she was very swollen in that area. My husband had experienced a similar swelling recently, and a barber plastered it for him.9In those days, barbers used to be surgeons as well. I called my maid and told her: “Go to Chaim in shul and ask him which doctor it was, where he lived and go there with the child so she can get the good plaster.” I thought nothing of the whole incident.

The maid went to the shul and asked my husband for the barber’s details. On her way back through the ladies’ section, my sisters-in-law, Yenta, Silka and Esther stopped her. “What were you doing in the men’s section?” they questioned. So she told them what had occurred, and the women became frightened because they were big alarmists and because we came from infected Hamburg. They put their heads together and discussed the situation.

In the shul there was a guest, an old woman from Poland, who overheard the ladies’ conversation. “Don’t worry,” she told them. “I have been working with such issues for twenty years already. If you want, I can examine the child, see if there’s any danger and tell you how to proceed.” They urged her to go see my daughter to ensure that they wouldn’t all be in danger.

The Child Is Sent Away

I was clueless about all that had happened upstairs. The old lady came downstairs and asked, “Where is the little girl?”

“Why?” I asked.

“I am a doctor,” She answered, “I will heal the child so that she will soon recover.”

I showed her the child. She examined her and fled for her life, straight to the shul. “Everybody out of here,” she announced. “Whoever can, should run, the child has the dreaded epidemic on her.”

You can imagine the chaos and fear she caused. Women and children ran out of the shul in the middle of the best tefillos of the Yamim Noraim. Immediately, the maid and the child were kicked out and nobody wanted them in their house.

It’s easy to picture my mood. I screamed “Rabbosai, look at what you’re doing. My child is healthy – she had a head injury in Hamburg before I came here and it spread and caused this swelling. When someone has the disease there are ten different symptoms, of which she has none. Look at my child – she’s running around on the streets and eating a roll.”

I begged and pleaded but nothing helped. They all just said that when the Duke will hear what’s happening in his residence, there will be severe consequences. The old polish lady, promised me her neck, if the child doesn’t have the disease. I begged, “Have mercy! Let the child stay with me. Where she goes, I will go, just let me go to her.” But all my screaming and beseeching fell on deaf ears.

My brothers-in-law R’ Avrohom, R’ Lipman and R’ Leib, sat together with their wives, to come up with a plan of where to send the maid and the child. Everything had to remain a secret from the Duke due to the great risk if he were to find out.

They came to the decision that my husband would dress my child and maid in rags and old clothing and take them to the village of Hainholz, near Hannover.10Today it’s a part of Hannover. They would present themselves to the village guest house and say that the Jews in Hannover were not willing to take them in over Yom Tov as their houses were already too full. Therefore, they want to remain here over Yom Tov and, of course, they’ll pay. The Hannover Jews will send food and drink because they wouldn’t let their brethren starve over Yom Tov.

In Hannover, there was another old person who we hired together with the first lady, to watch over the child and see how the infection develops. Both wouldn’t budge before being paid thirty Reichsthaler, since they were putting themselves into danger.

My brothers-in-law sat with the tutor of Hannover who was a big lamdan and they decided together that due to the dangerous situation we were allowed to give the money on Yom Tov.

In the middle of Yom Tov, we had to part from our beloved Tzipor. Every father and mother can imagine the aching pain we felt all Yom Tov. My husband and I stood in separate corners and cried and davened. It’s surely in the zechus of my frum husband’s tefillos that Hashem helped us.

I don’t believe that Avraham Avinu at the Akeida was in more pain than us. He was commanded by Hashem and could therefore do it with joy, but we were in a foreign place, so full of sorrow. But what does one do? We thank Hashem for the good as well as the bad. I dressed the maid in old clothing, put essentials for Tzipor in a bag, gave the child old rags and sent them off, looking like poor beggars. Together with the old man and lady, they left for the village. We parted from our precious child with endless blessings and copious tears.

The child however was content and even excited, for there was little she could understand. They were warmly welcomed in the village and taken into a guesthouse. Alas, all of us in Hannover were sobbing, full of pain and the rest of the Yom Tov was spent in great sadness.

Food is Delivered

We went back to the shul where obviously the tefillos were already over. At that time, R’ Yehuda Berliner was in Hannover along with a bochur from Poland named R’ Mechel, who was employed to learn with the children. He eventually married, had children of his own and remained employed as a tutor, which earned him a good parnassah. He was also a half servant at the time of his employment as a tutor, hence he had two duties to fulfill in one household. This was the custom then in Germany.

As soon as we left shul, R’ Leib invited us for the meal but my husband insisted that we cannot eat before our child gets food.

“Definitely,” they responded. “We will not eat until they are given food.”

The village was pretty close and we put together a sack of food.

When we asked for a volunteer to deliver the food, everyone said no, until R’ Yehuda announced, “I will take the food,”

“And I’ll go along,” R’ Mechel said.

My husband was insistent on going because the love for his child was so strong, but the Hannover people were worried that he would be unable to control himself and touch her. So my brother-in-law R’ Lipman also went along, and it ended up being a whole group of them.

They found the child strolling in the village and as soon as she saw her father she wanted to come running. R’ Lipman signaled that they should keep her away and the old man should take the food. My husband had to greatly control himself from hugging the child who looked completely healthy. They left the package of food and drink on the grass and then returned to Hannover for the seudah.

This arrangement worked until Shemini Atzeres. The old man and lady plastered and creamed the wound until it healed completely. The child was also hale and healthy and jumped around the fields like a young deer.

We approached the Hannover crowd and said, “Why continue with this? You see our child is perfectly healthy and is no danger for you. Let my poor child return.” They gathered again and decided that before Simchas Torah they cannot let her back. What could we do? We had no choice but to agree.

Before Simchas Torah, R’ Mechel went and brought her and the maid back to Hannover. The simcha in the city was tangible. Everyone wanted to see Tzipor, who was an exceptionally special child, unlike any other. After this incident she remained nicknamed, ‘The young lady from Hainholz’.

Image Information:

Title: Zichronos Mrs Gikel Hamel – Memoires of Mrs Glückel Hameln

Publisher: Dr. David Kaufmann (1852–1899)

Edition: First Language: Old German Yiddish

Publishing location & year: Pressburg 1896

Image Information:

Artist: anonymous

Title: Portret Jana III na tle bitwy – Portrait of Jan III on the background of the battle

Description: Portrait of John III Sobieski (1629-1696)

Date: fourth quarter of 17th century

Collection: Palace Museum in Wilanów

Accession number: Wil.1961

References: Museum of King Jan Iii’s Palace at Wilanów

Everything Is From Above

From this short and heartwarming diary excerpt, we get a glimpse of several aspects of life in those times:

We see the fear that an epidemic caused and the lengths to which they went to protect themselves, even when there was just a tiny chance that someone was infected.

We also see the inner strength of a Yiddishe mama. Glickel could have been angry at the Polish lady, at her sisters-in-law, or at the citizens of Hannover, yet she only saw one thing: “Just as one recites a blessing over the good that befalls him, so does he recite a blessing over the bad.”11Berachos 48b.